I was rummaging through the attic at my ancestral house, years ago. The house was one constructed when attics were must-to-have unlike the ‘attached bathroom with a shower’ and ‘Bombay latrine with a commode’, both being novelties and were nice-to-have then. There was no standard procedure to define what all could be stored in the attic. One could find for sure old earthen pots, brass tumblers, wooden ladles, lyric books of movies released sixty years ago when Indian talkies were ‘sing-ies’ with more songs and less dialogues.

To a fortune hunter with a missionary zeal and monk like patience, the attic would also yield treasures of the unexpected kind like late Victorian erotica in chaste English, with the characters addressing each other ‘sir’ and ‘madam’ and profusely thanking each other on completion of the intended amorous act, strictly according to the book.

… …. …. … .. .. .. .. .. ..

— — — — — — — — — — — —

Another gift of the attic was old mail. This was of the vintage post cards kind. Many such yellowish brown rectangular cards were there, all addressed to my grand father who was the head of a large joint family living together in peace at our ancestral home. The cards were all covered in a coat of dust that somehow acted as a deterrent against their getting decimated and devoured by pests. Nearly fifty antique mail were there, impaled on an evil looking steel spike with a flat cast iron bottom.

All the letters I retrieved were written by a single person, perhaps the first writer in our family. I was given to understand this one was a great grand cousin of mine.

It appears there prevailed some unwritten code of conduct which would have dictated that at least one person, male only that is, from each middle class joint family at some point of time in his life should renounce the family ties and walk out unannounced of the household, mostly by night. He would be mostly taking such an unceremonial leave of his close relatives that included his wife and children as well, only to return after a decade or more. My great grand cousin (GGC in short) strictly would abide by it.

The most interesting thing about this GGC is that he was a confirmed bachelor who went out at noon on a hot summer day, never to return. He left in a huff after someone hinted half playfully at lunch time that he did not make any attempt to settle down in a job even three months after passing his school final examinations but was settling down to a life of lunch – siesta – dinner – slumber. The immediate provocation I learn was that there was a job vacancy for a book keeper in a hotel that sprang up near our place. The GGC was deeply hurt that he was expected to take up the demeaning job of a hotel clerk doubling up as a cashier and in all probability, as one waiting at tables downstairs, when the occasion demanded. All these happened in early 1940s and the letters were penned by him to my grandfather, the fugitive’s uncle who brought him up, being orphaned at a very young age.

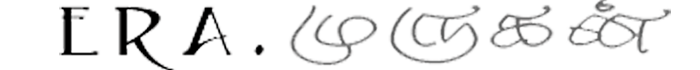

I removed the bunch of letters from the spike and pulled out an epistle from the collapsing card pack. It was dated 1st April 1940.

‘I am not fine but am suffering, here, in Alappuzha’.

The letter writer began with an ominous note, quite unlike the conventional letter writers. Having set a wailing tone, he proceeded to elaborate upon his hardships. These prima facie were the cascading effects of his unscheduled jaunt to the neighbouring state of Kerala from Madras presidency, though not appropriately acknowledged by the writer. Having arrived at Alappuzha, the coastal Kerala town by train that reached the destination late by a full ten hours, he attempted to get a decent boarding and lodging. As luck would have it, all he could get was a bed bug infested lodgement to stay at a very high tariff and insipid, stale food that had grounded coconut added to all food items, even to fish and chicken, as the GGC claimed.

He blamed my grandfather squarely for his plight. The latter, he accused, did not arrange for his study in college but wanted him to be an accountant in a wayside hotel and that was the source of all the GGC’s misery. The patriarch was requested to send at least twenty rupees by telegraphic Money Order to the GGC’s hotel address immediately on receiving the letter, to tide over the crisis situation.

(continued in The Wagon Magazine – Feb 2017 issue)