A short story from my collection, The Polymorph

The Bottle

The ferry was on the other bank of the river.

At least twenty, all men, were there at the boat jetty along with Kesavan, waiting for the ferry to arrive. Except Kesavan and a shabby-looking elderly person with crutches held under his arms, others had reached there on their motorcycles. They all had to cross the river with their vehicles too being ferried along with them. Parking their motorcycles near the small shop with thatched roof, a little away from the river bank, several of them were treating themselves to glasses of cold sweetened lime, available in the shop at twenty-five paise a glass, as a small display board at the front of the shop informed. Few of them followed that with a leisurely drag on their cigarettes also purchased at the shop while others resumed reading their newspapers, perched high on their motorcycles. None exhibited any urgency to cross the river immediately, Kesavan observed.

It might be all right that none of them had to hurry up. But why should they all opt for the sweetened lime drink as if sentenced to gulp it down when they had nothing else to do? They could for a change taste the new chilled soft drink launched nationwide last month by the country’s largest food and beverages manufacturer, for whom Kesavan worked. That multinational company had a wide global presence and their branded soft drinks were the most favoured of all age groups except the infants and toddlers, everywhere. They were being consumed with verve all twelve months of the year and throughout the day, everyday.

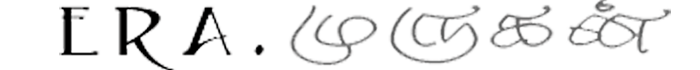

Aha, fizzy ambrosia .. Someone somewhere opens a bottle now!

Kesavan impulsively was humming the advertisement ditty for the newly launched soft drink. It was created for radio advertisement of that orange drink and was fast becoming popular among the below-thirty age group, enjoying a good general brand recall value with the general public too as such.

The old man sat on the ground with his arms kept protectively around a jute sack, like holding a child with all affection and care. He looked at Kesavan with little interest.

“It hardly takes five minutes to cross the river. But the ferry is yet to come, even after waiting for half an hour”.

The old man sounded complaining, as he spoke to Kesavan. Kesavan was happy that apart from him, the old man too was keen on reaching the other bank at the earliest. He also did not make a beeline for the sweetened lime drink like others.

“Everyone appears to be laid back”, Kesavan responded to him waving his arm towards the ferry at a distance, on the other bank. He was a little hesitant to share his observations with a stranger as it might be overheard by others at earshot, who could misinterpret what he said and would mysteriously feel offended for whatsoever reasons they only would know.

If the arrival of the ferry would be further delayed, there was a remote possibility that several of them bored utmost with the lemon drink could turn curious to taste for a change the soft drink Kesavan’s company had launched new in the market. It was available everywhere including the tiny shop near the river bank. He had checked its availability there when he reached the boat jetty.

It appeared to be an unwritten duty of Kesavan to promote the newly launched soft drink anywhere, anytime and through anyone, walking the extra mile when required. And that would justify his getting paid his wages without fail every month. He had to cross the river to reach the accounts department of his office to receive the wages, disbursed today, though a holiday. They worked overtime on the first Sunday of every month to complete all accruing accounting work due to the new product launch. They were perhaps adequately compensated with additional non taxable benefits for that, as Kesavan understood. It could perhaps be in the nature of free delivery of crates of the newly launched orange flavoured soft drink, to them. If the ferry did not turn up soon, the whole accounting department might as well leave for the day making Kesavan near broke.

“Everyone appears to be laid back as this is a Sunday”, Kesavan reiterated with an emphasis on the day it was.

“What is special about Sunday? For all those employed, working days and holidays abound. For others like me, it is the same every day”.

The old man told Kesavan. Squatting on the soft sand and with his hands firmly gripping the ground, he moved towards the water front. Having accomplished that, he threw the crutches away on the bank and held his swollen feet dangling onto the stream, getting wet with the water flowing down.

Kesavan thought the crutches might have been very painful to the old man and the very prospect of having them always with him would have irritated him as well.

Someone peeped out of the window of the engine room of the ferry anchored on the other bank and shouted something. He was incomprehensible to all those assembled there. They stared at him for a second and then continued with sipping their next lime drink or reading the newspaper they were engrossed in or staring silently at the horizon.

“What does he say”?

Kesavan enquired the old man, pulling out the cigarette pack from his shirt pocket and lighting it.

The old man hurriedly moved, grabbed his crutches lying nearby and placed them on his lap like a child, patting them. His hate or other negative feeling towards them would have subsided and they would have again become likeable. The jute sack was also tugged towards him. Had it been pulled a little more in, it would certainly have fallen into the river.

“It appears the srank*** of the ferry is informing there is a problem with the outboard motor”, the old man said raising his voice a little. He might have wished others there should hear what he was saying. However, except for Kesavan, others did not even turn towards him. (*** Srank – navigator)

“Are you able to grasp what he is shouting at that distance?”, Kesavan asked the old man in a half-convinced tone, while offering him a cigarette.

“No, I don’t smoke. I was once smoking beedis. But I gave it up when my own boat went out of service. Don’t we need money to buy the pack of beedis, however small the amount is? No one throws a beedi or the extinguished stub to be picked up and relit by rag pickers. They extinguish it half way through and keep it tucked safe up their ear, for future use”.

The old man laughed. He was once a boatman rowing a tiny boat when his arms and legs were strong, Kesavan observed. If somehow a boat could be arranged for now, he could ferry himself and Kesavan across the river without any need to wait further.

He looked at the old man with a new found respect. The elderly person could as well be knowing how to swim too. Kesavan could not.

“Where were you a boatman?”

Kesavan threw the cigarette butt into the stream and asked. The old man was staring at the stub glowing like one at the end of the life. It appeared to Kesavan he did not approve of his throwing the cigarette stub into the river. Kesavan bent forward and tried to retrieve the stub, but it swiftly moved away dodging him, towards the centre of the stream.

“Leave it. If you bend too much, you may fall into the flooding river. It would then require the services of someone else to save your life”. The old man casually observed. Kesavan was surprised how he knew Kesavan could not swim. Perhaps his awkward action in trying to fetch the cigarette butt from the water made him guess so, correctly though.

A loud thud was heard at the other bank. A young man, barechested and wearing a pair of bermuda shorts, jumped from the ferry into the river and started swimming across the river.

“The river is deep at many spots here. Also, the riverbed is sandy. You may get trapped easily”, the old man murmured.

“They should then construct a bridge over here. Why did no one have a thought about it till now?”, Kesavan enquired.

“They indeed had commenced that long back. See there”.

Kesavan looked at the direction the old man waved his hands at. A partially constructed platform was seen protruding from the riverbed. It looked more than a decade old with green alge appearing as stubborn patches on it.

“What happened”, asked Kesavan. “Is the construction delayed?”

“Delayed? It was given up. When the Government which began the construction was voted out of power, the incoming one set up an enquiry commission to investigate charges of corruption in awarding the contract for bridge building. It never took off again”, said the old man with a sigh. An instant later he was laughing with abandon.

“It was good the bridge did not get completed. I and two others like me ferried passengers across the river at this place, for a small fee of ten paise. We all had a steady income, be it summer or rainy season”, the old man observed with a tinge of nostalgia.

Someone turned the ignition of his motorcycle on, raising the throttle. The roar of the automobile engine drowned the old man’s voice mid way through.

Kesavan was a boy of ten or even less when the ten paise coins were withdrawn from circulation as their purchasing power was almost nil by then. The old man was collecting ten paise as his fee which would mean it was a good period for those coins.

“As the construction came to a standstill, the Government commenced a free ferry service. It was election time then. Do you remember all that?”.

Kesavan was clueless about all that. That would have occured well before his birth, like many other things he was unaware of.

“Are you going for the Mass at the other bank?”, the old man enquired lowering his voice.

Kesavan, who did not anticipate that question from the old man, was silent for a moment and then replied in the negative, which sure would have disappointed the old man.

He opened his jute sack a little and showed what was there in it, to Kesavan. Kesavan observed that it contained mostly broken glass pieces. Kesavan knew what those thin glass fragments were.

“If you offer prayers there at the Mass, all these broken pieces would fuse into whole glass bottles again”, the old man lowered his voice still and said, looking deep into the eyes of Kesavan.

Kesavan on reflex nodded vehemently indicating that could not be so. His eyes were staring at the river with a trace of guilt in not accomplishing a task he was entrusted with, in its entirety.

The old man pulled out from the innards of the jute sack an old bottle. It was a container the small players in the soft drinks market would normally pack their drinks in hues of gaudy red, pale yellow and pink, for retailing in rural and downtown areas. Kesavan was familiar with the bottle in its homogeneous form, unlike this one appearing as several glass pieces stuck together.

“How is it that this bottle appears made with pieces retrieved from different bottles?” He asked in a voice that sounded a little relaxed than being earnest.

“Yes it indeed is. Yet, this is saleable. They eagerly buy it for fifty paise to carry home the divine water after the prayers, for their folk who could not attend”.

Kesavan would be offering prayers ashore for the betterment of the society, after he received his wages for the month it was. Those prayers would ensure those who would be waiting here then on, riding their motorcycles, would board the ferry without much waiting. Some of them would as well aspire to partake a glass of the soft drink his company retailed, upon crossing the river. It was the one available in the market at the most competitive price, was popular internationally, liked by all across ages and sipped all through the day and night with gusto, following the Sun or going on the reverse.

“If only the ferry arrives now, I can make about five rupees from what is available in the sack. The Mass should not have come to a close before I reach there”. The old man sighed.

“Where do they conduct the Mass?”, Kesavan asked.

“In an old building over there”, he waved at the other bank. “The building is so small that not more than twenty can be there inside, sitting cramped. Whenever I attend, I have to stand out only. If only I get an opportunity to go in and join the prayers .. these glass pieces will then turn into bottles originally made and not like a hybrid one with different sources that they are now. Those born anew bottles would easily fetch a rupee or even more. The ‘soda factory wallahs’ themselves would like to acquire the empty bottles from me, for reuse”.

The old man still had a glimmer of hope left in him. One of these Sundays he would attend the Mass in time. He would then commence walking again and would not need the crutches anymore. He would carry another sack as well to get more bottles evolve into freshly manufactured homogenous containers. For all that to happen, the ferry should come.

The old man opened his sack again and took out two croissant buns packed in a dirty brown paper bag.

“Long back, I used to reside there near that tall building on the other bank”, he said as he pointed his finger at a distance across the stream. He started munching a bun with relish as Kesavan looked at the tall building. He intended to go there only. His office functioned from there.

“I had an abode offshore. It was not a proper house build with brick and mortar but a hut mostly, with an enclosing wall. Whenever I cross the river, I go there and stand silently for a few minutes, looking at nothing over there in particular. I go to the Mass after that only”.

“Who resides there now?”

Kesavan was keeping the communication alive with the old man. To reduce the tension arising out of the delay in the arrival of the ferry he had to pass time speaking to and listening to someone.

“It simply does not exist and as such no one is there now. I had a small boat then. I had my wife with me. My limbs were strong to row the boat from there to here and from here to there throughout the day. None of that exists now. My wife too passed away”.

Kesavan wished the miracles to duly happen in the case of the old man, bestowing him with homogeneous bottles to sell, with strong limbs to walk and run and with the house on the other bank reappearing somehow. But what about his wife? Can miracles revive the dead?

“Barely an year ago, she was with me accompanying me while I was busy rag picking, wandering through the town. What all I could get to eat, I shared with her. Hungered and fatigued, we slept on the facades of the shops shut for the night, till the policemen would rudely awake and would drive us away. She passed away one night in her disturbed sleep but I slept sound that night beside her and would know she died, only the next morning”.

Kesavan was undecided what should be his response now. He silently lit a cigarette, extinguished the match stick and kept it on the nearest stone slab at the boatyard.

“Near where my hut was standing, is the shop dealing in old locks and keys. You can also get bottle caps and cork stoppers from there. I would always buy a few of the caps and keep them in my sack beforehand. Somehow, the rummaged bottle caps do not fit perfectly the reconverted bottles and we have to go for new caps only. As the full fledged bottles evolve unattended in my jute sack, I would close them securely with the new caps as appropriate. Having done that, I would sit at the front gate of the prayer building, vending the ware, calling aloud, “Blessed bottles for sale”. It may as well be nightfall when I would get buyers for all the recreated bottles. Yet they come without fail. Then I would return here and would take a bus to the town to resume rag picking. Even otherwise, wandering keeps me alive. What do you do for a living, sir?”, the old man spoke at length supressing a cough and ended up with a question tossed at Kesavan.

Kesavan smiled. He then mentioned the name the food and beverages manufacturing company he worked for. “Are you an officer there?”, the old man asked. “Yes, I am”, said Kesavan.

Kesavan was designated as an executive by his employer. An executive would also be an officer who officiates as a performer of all assigned tasks and more so, a manager who manages the entire bandwidth of activity, he knew. It would be the duty of the manager to travel within the target area and procure all the stock of the soft drinks made available for retailing by the worthless local competitors. The procurement would be inclusive of the containers, at a somewhat exorbitant price, being one-off. He, the executive would empty the bottles down the flush and would then smash the empty bottles to the floor breaking them into pieces. The odd sized glass pieces always gave him a sense of job satisfaction, giving rise to a feeling of quelling the competition. Consigning the glass pieces to the bin, it would also be his duty to continue his initiative at the next town or village on his chartered route, often covering a whole linguistic province.

Hereafter he would expend more efforts in breaking the bottles into still much smaller pieces so that no amount of prayer could get them reconverted into whole containers.

“The primary reason for the wretched local players to come up with their crude sugar water versions of soft drink and launch that in the market at dirt cheap prices is the easy availability of glass bottles. If we could acquire all the glass packing material down the supply chain and cast it away, they will immediately shut shop. We then will mark this territory too conquered”.

Kesavan remembered the induction programme he participated when he joined the company. He was at times feeling a little ashamed to knot his neck tie into a double knot and wear a blazer before starting work for the day that was to visit village after village in his so called command area. But his mission was unique he strongly believed.

If the ferry would arrive, if only he would cross the river, if he would enter the tall building near where the old man’s hut stood once, if the office would still be open, he would submit his accounts. He would be promptly paid his wages and allowances as laid down in his contract for employment. He would also receive the medical allowance for getting medical treatment for the bruises he had incurred on his left arm while breaking the bottles last week.

The lad who swam from the other shore now reached where Kesavan and others were standing.

“The engine of the ferry is still having the snag, we are attending to. We shall strive to restore the service at the earliest. You can please leave now”.

He announced loudly twice and jumped back into the stream. He could be seen creating waves as he swam across swiftly back to the other bank.

Those who came on their motorcycles were returning in ones and twos. They all appeared like they were there only to have a sweet lime drink or to light a cigarette or chat with others, mostly strangers. They seemed to be contented that they had achieved the purpose of their visit and as such they bore no grudge against anyone. They honked the sound horns of their vehicles playfully as they went off.

A young men alone who was perched on his motorcycle, reading a newspaper was still engrossed in his reading unmindful of the surroundings. “He will leave only on reading the last page, last column of the newspaper”, Kesavan said somewhat loudly to the old man, unmindful of the slight increase in his voice level.

“Let us too leave. I’ve to wait till next week end, it appears. I can get from the garbage enough material to recreate five or six bottles by then”, the old man observed, standing up clumsily with his crutches kept in place under his arms. Kesavan too stood up. He helped the old man to carry as a back pack, the jute sack.

“What do you do with the broken bottles, in your company?”

The old man, walking with the crutches firmly held under his arms stopped for a second, turned around and enquired Kesavan.

“Those bottles never break”.

As Kesavan said this, he felt sad.

He looked at the tall building at the other bank and walked slowly away.

(The End)

———————————————————————————————————-

to acquire the ebook ‘Polymorph’

———————————————————————————————————–