Everything about Chennai Pattinam amazed Sankaran. The streets were countless, snaking across each other in complicated twists and always full of traffic. The smells of horse and cattle dung, jackfruit and roasted grain and jasmine, sweat and urine, mixed to produce a compound city smell that pervaded every lane and corner. And everywhere there were men busily going about some kind of business. The horse carriages of the white people ran on the wider roads and there were the more private, shaded roads where the western women walked, protected from the sun by their parasols. Then there was the Black Town where lived the families of Indians who worked solely and proudly for the white people—they and their children after them. Both Tamil and Telugu were heard equally frequently from the houses he passed. Eateries did brisk business at every intersection.

Sankaran had never experienced urban life of such a nature. He had seen Jaffna and Madurai, but they were like tiny villages compared to Chennai.

And then, there was the sea, and the immense stretch of the beach. After he got married, he should bring Bhagavathy Kutti here. In her sixteen years, exposed only to the rivers and fishing boats of her home, she would have never seen anything like the vast beach of sandsea. He would like to walk with her on this beach, their feet sinking softly into the sand. When they grew tired of walking they would sit down and he would listen to her sing. Her voice would rise above the roar of the waves. Salt spray would sprinkle their faces and Bhagavathy would lean her head against his shoulder. But would she be able to strikehold erotic poses like the Kottakudi dasi, a small voice inside his head asked him mischievously.

‘Master Iyer, are you daydreaming? Are you making plans to build two huge buildings on the sand, one for selling snuff and the other for selling tobacco?’ Karutha Ravuthan teased Sankaran and laughed loudly.

Karuthan laughed frequently and loudly. He was the son of Pichai Ravuthar of Bangalore, a good business friend of Subramanya Iyer.

‘Karutha, I have told you so many times not to call me Master. Call me Sankara, or if that is difficult, call me Sanakara Iyer.

‘How can I call a Master anything but Master, Master Iyer?’ Karutha laughed uproariously. Over the last three days, Sankaran had got used to his levity.

Subramanya Iyer had insisted that Sankaran go to Chennai. ‘I can’t bear to see you like this, Sankara. You are just sitting around moping. Saama is gone and will not come back. Those he has left behind have to get on with their lives. You haven’t stepped into the shop and you don’t talk to anyone at home. On four occasions Ayyanai has brought you back from outside the old house where you just stood staring at that burnt pile. This will not do. Go to Chennai Pattinam, Sankara. The sea breeze will do you as much good as the change.’

‘What will I do there?’ Sankaran had grumbled.

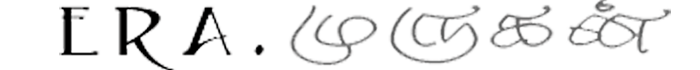

‘Learn the snuff business. Pichai Ravuthan’s son has opened a shop exclusively for snuff in the Ex… Ex… I can’t pronounce the name of the place.’

‘That is the Esplanade,’ old Subbamma said clearly, adding, ‘The ancestors have all come to bless you.’

Overcome with joy, Iyer folded his hands in obeisance to them.

Behind him, in an inner room, Kalyani lay moaning. She was bedridden since she had heard about Saama in Madurai. Her sorrow afflicted her in bouts. She would lie dead to the world for hours. Then she would suddenly sit up and plead loudly, ‘Saama, my breasts ache, drink the milk from them, child. Saama, prostrate before the elders with your wife. Sit down on the swing. Somebody give the couple milk to drink and plantains to eat… Have the pillows for their bed been stuffed with the softest cotton?’ She would ramble on loudly for a while